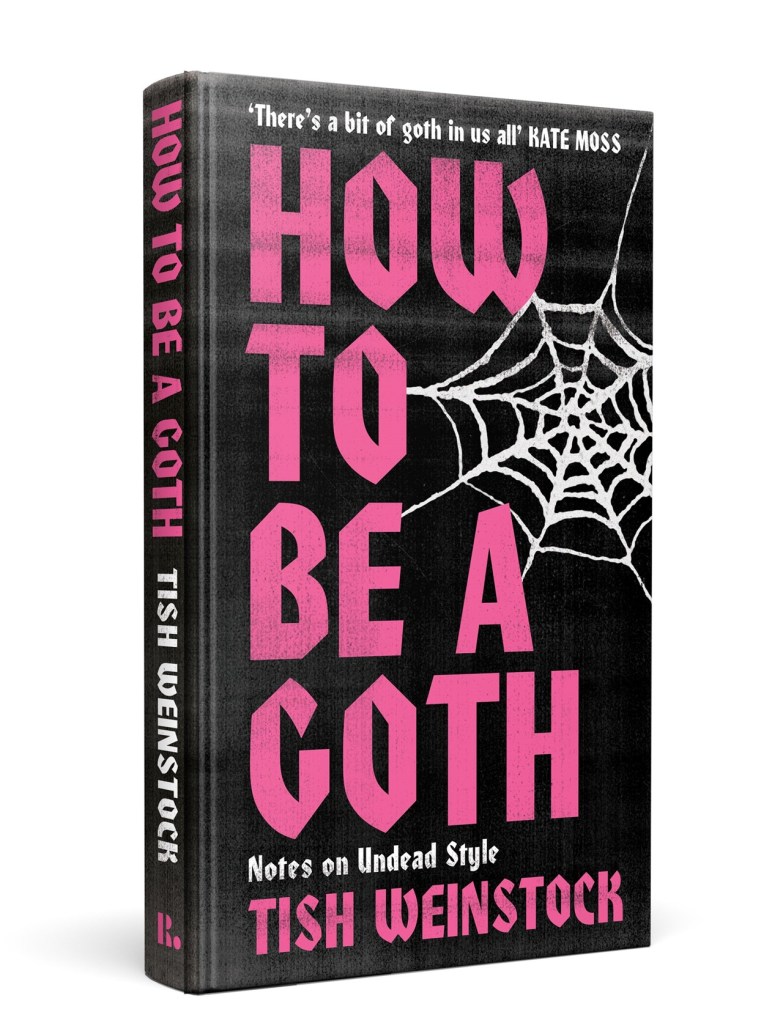

Goth is a niche interest. No, it really is – and it used to just be nothing more than fleeting infatuation from high fashion every year, as the season turned chill and the catwalks cried out for inspiration. I called it the Dark Wash Cycle and have filed several tired dismissals previously. Until now, when a Beauty Editor at British Vogue has decided to turn in a whole book on the topic…

Firstly, my sincere thanks to the staff at Octopus Press who rushed a pristine hardback to me swiftly after enquiring if I could get a review copy. Appreciated!

I predict this article will very quickly get mired in questions of legitimacy and gatekeeping, not to mention the swamp of despair that “What is Goth” has always been. I’m going to refer back to the definition on this page, and reiterate my argument that goth is mainly defined by – ironically enough – the opinion of the masses. If the loudest voices in our scene, the online goth community, judge in favour then I believe you can tentatively assume the mantle of goth. If, as with How To Be A Goth: Notes On Undead Style, you instead fall foul of the Great Online Goth Cabal then you’re going to have a hard time establishing any goth credentials at all. You can’t even invoke the Eldritch Exception Act and just deny all association, hoping to gain credibility by reverse psychology!

But, and this is a crucial point, I believe Tish Weinstock’s book isn’t for goths. It’s for another very niche group – a consumer group with actually disposable income, looking to rebrand on the back of a cynical commodification of the goth subculture. Which also allows How To Be A Goth to distinguish itself from predecessors like Goth: A History, Art of Darkness and Season of the Witch – except where the title of Cathi Unsworth’s book pops up three or four times in Tish Weinstock’s, including on the back cover. Well, nobody owns a phrase like nobody owns the colour black, but I wonder if it was author or publisher who decided to incorporate such a textual hook!

Tish’s own personal intro is very familiar – a personal feeling of alienation from a young age, leading to a chance encounter with some landmark representative of dark culture that sends one down the slippery slide to gothdom. The usual slew of 90s bonafide goth classic movies then – Edward Scissorhands, The Crow, The Craft and of course Barry Sonnenfeld’s landmark The Addams Family whose vampiric matriarch Morticia Addams obviously resonated with our author in her youth! She namechecks the authors, actresses and musicians you would absolutely expect to be on any emerging goth’s checklist, but also delves deep on the artists that inspired her, and lingers longer on finding her style as an unruly teenager – which obviously prompted her subsequent career in fashion journalism.

Then we’re off into the ‘Brief History of Goth’, and I do appreciate the brevity of her chapters – she writes with the discipline of a seasoned columnist that is all at odds with the sprawling, endurance challenge that was getting through The Art of Darkness. Unfortunately, concerns are raised when – as soon as page 12 – we learn that Bela Lugosi’s Dead by Bauhaus, arguably the most totemic song in goth music history, was released in 1982. Except, it wasn’t – it came out in 1979. To stumble on such a basic, well-known and easily researchable fact will not endear those readers who are steeped in the history of goth music – and especially not the nearest thing we have to an executive body, the notoriously arch-conservative members of r/goth.

This of course opens up the antique can of worms that contains meaty words like ‘elitism’ and ‘gatekeeping’. In a subculture meant to be open and accepting of others, should we judge writers like Weinstock for not being au fait with the soundtrack? Is that a prerequisite for goth ‘acceptance’? Is there meant to be a goth entrance exam? As I said at the start of this article, those are good questions that deserve answers – but crucially, again for those at the back, this isn’t a book for goths! It’s a fashion journalist’s approach to goth style, it says it in the subheading and everything! So it could be that you could take the eminently sensible approach, jettison all questions of goth ‘legitimacy’ and accept the book for what it is – a consumable, emerging from the corporate entity that is publishing.

Weinstock writes faithfully from her experience as a fashion journalist, claiming that “From the runway and the red carpet to the internet highways via the street, gothic fashion is having a revival”. This stands in jarring contrast to the increasing glut of these types of article claiming a goth ‘renaissance’ – I’d argue it hasn’t been out of mainstream influences for a few years now! At other teams, the author is more perceptive, noting that in the 80s heyday of ‘traditional’ goth,

“Although no goth wanted to look like another, there were obvious style codes; a DIY mix of historical costume and notes of BDSM. Fast-forward to today’s post-subcultural landscape, however, and things are much more fluid”.

Despite fervent protests online, it can be argued that we are post-subcultural – no longer beholden to a monolithic social group, but instead mixing-and-matching to create individualistic styles personal to ourselves. This is even more pronounced in goth, a scene so lacking in formalised expectations and yet awash in indignant judgement! Goth should absolutely expect this kind of reinterpretation and reimagining of its iconic look. Weinstock also surprises when she recommends a more economic and DIY approach to outfit sourcing, that sits at odd with the high-cost, high-fashion world she normally inhabits. But, it is good advice!

Reinforcing the ability to reinterpret goth – and infuriating the dyed-black-in-the-wool traditionalist readers – Weinstock observes that “Back in the 80s, to be a goth mean to adhere to a set of shared, albeit unspoken rules. But in today’s post-subcultural world, to be a goth you no longer need to listen only to goth music, hang out in goth clubs or dress strictly in black…you can dip in and out of the culture as you please. It’s about being goth-coded.” I can hear the grinding of custom cosmetic fangs from here, and remind the staunch standard-bearers of post-punk that if the casual visitor to goth isn’t actually visiting the clubs or listening to the music, at least there’s little chance your paths will cross!

Elsewhere in the book, Weinstock hails her ‘Gothic Heroines’, combining vaunted actresses, fashion titans and soundcloud music stars who have all dabbled with darkness. On contemporary model Gabbriette Bechtel, she writes “With her liquorice locks, smudged charcoal eyes and trademark lobotomized stare, she oozes a stygian glamour”. Personally I prefer the basilisk glare of a Diamanda Galas or the sultry power of a Patricia Morrison – who does get her accolades alongside other icons like Siouxsie and Poison Ivy, later on. When quoted herself, Bectel neatly sidesteps the debate and correctly observes to Weinstock later that “Goth is something you can’t define”.

I enjoyed reading the author’s summaries of the complex lives of fashion house royalty like Isabella Blow and Alexander McQueen, whose personal lives were gothic tragedies as much as their ornate personal and professional styles. But I cringed over her picks for “Undead Men – goths to get out of the grave for”. I rolled my eyes at the description of Andrew Eldritch as a ‘wicked warbler’, picking both Bela Lugosi and Gary Oldman’s Dracula feels like grasping at any icon going – and my sincere apologies, but Ian Curtis is nobody’s pin-up.

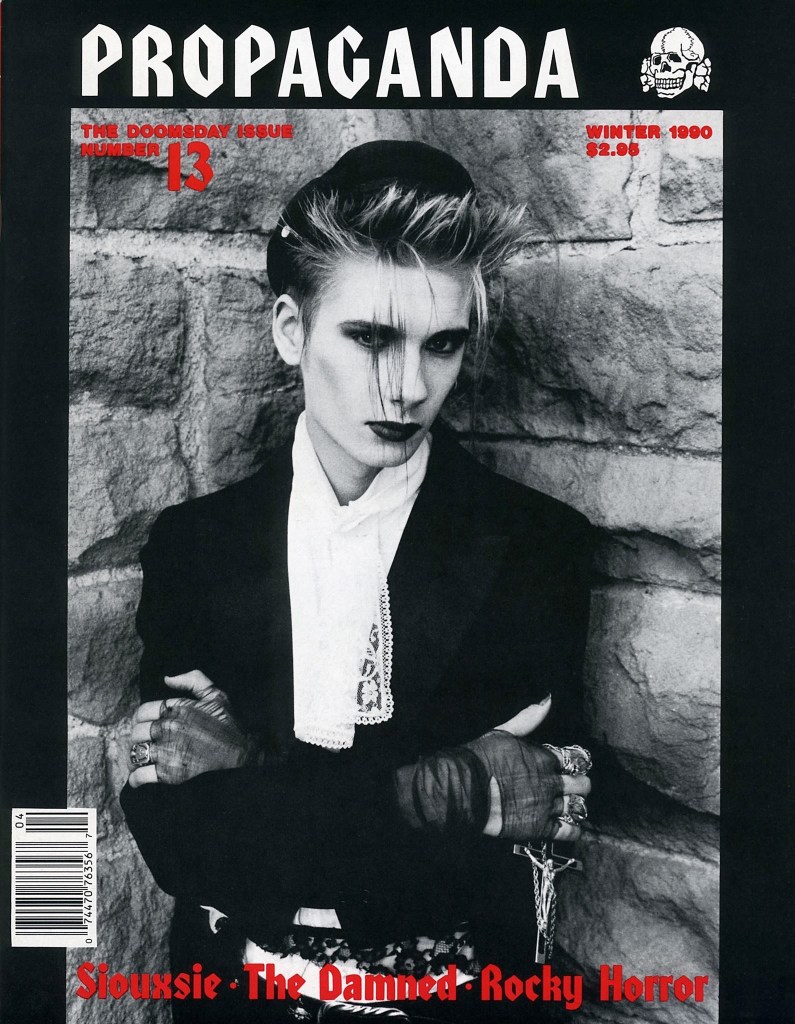

Her book picks are a solid recommendation list, from old reliable choices like Walpole, Baudelaire and Poe to newer recommendations like Gibson’s Neuromancer, Ellis’ American Psycho and of course Propaganda, the iconic bible to the American goth scene for two decades by Fred H. Berger. Elsewhere, Weinstock makes some recommendations that are actually fairly sensible but seem provocative on first glance – when advising aspiring goths as they advance from adolescence into adulthood, she cautions them to “Think less Siouxsie Sioux and more Susie Cave”, which might have the more committed members of our scene reaching for the unholy water. But there is a case to be made for a more nuanced wardrobe that isn’t always on the extreme end of sartorial challenge, and there’s no undermining the alternative credentials of The Vampire’s Wife – even if the author does refer to her husband as “post-punk’s Prince of Darkness”. Indeed, Susie Cave is the best representative of this occasionally uneasy melding of hypercapitalist high-fashion and anti-mainstream style challenge, the strange overlap that underpins this entire book.

Towards the end, Weinstock waxes philosophical and I am intrigued and in agreement with her observation that “we are hurtling towards an apocalypse … these are the conditions in which the humble goth tends to flourish”, evoking memories of the similar death-watch attitude of the scene’s 80s golden age. She also predicts that an increasingly complex society of broader and broader tastes and perspectives will mean goth will drift ever closer to normality and acceptance. It will cause those comfortably settled within the subculture to become less noticeable for their aberration, and less subject to derision, even as it encourages the truly boundary-pushing participants of our scene to go even further with their subversive activities!

I’d say that has already begun with revolutionary creators like Parma Ham – and the impact of such redefinition on this amorphous subculture, policed by ever-frenzied gatekeepers, will be something else to behold! Weinstock muses on what is truly next generation of punk rebellion, when we start to reject the very intrinsic nature of self and start ‘biohacking’ our bodies and redefining what it means to be human. Posthumanism is some heady stuff for a book ostensibly serving as a guide to goth style… but in the dying gasps of her work, Weinstock fumbles and falls back on trite, empty phrases perfect for column inches – “expressing your true self”, “possibilities are endless”, and of course “the season of the witch is far from over”.

I didn’t dislike “How To Be A Goth” – there’s some shining points to recommend it – but I do find myself returning to wonder who it’s for. Most goths will laugh this out of their (haunted) bookshop, and anyone looking to dip a toe into the scene based on these recommendations will meet with a frosty reception. Perhaps that’s a cautionary tale for the goth subculture – to be more friendly and offer polite corrections to the slightly skewed views herein?

Instead, this book is probably best bound to occupy an eye-catching spot on an influencer’s upcycled shelves, a light read for a Delia Deetz rather than the goth grimoire to be treasured by a Lydia. Strange, and unusual though it is!

The Blogging Goth is proudly supported by its Patrons – I couldn’t do this without your generous support. To find out more about keeping The Blogging Goth ad-free, and what unique benefits you get as a Patron, please visit my page!

Vaughan Allen

Claire Victoria

Mark Chisman

Pingback: How to be a Goth (Weinstock) – Schwarze-Szene.net